Defining Sustainability: The Different Approaches

Sustainability is a complex concept with multiple layers and interpretations. At its core is the notion of ensuring that our current actions don’t compromise the ability of future generations to meet their needs. However, defining and operationalizing sustainability is far from straightforward. In this article, we will explore the different perspectives on sustainability and unpack some of the key debates around weak vs strong definitions.

Balancing Needs and Regeneration

One of the classical definitions of ecological sustainability proposed that three principles must be balanced: 1) harvesting renewable resources at rates lower than regeneration, 2) waste assimilation matching environmental capacity, and 3) substituting non-renewables with renewables. This touches on ensuring that what we take from nature can be replenished over time. However, it doesn’t address the interactions between these different components or how human and natural systems interrelate.

Weak vs Strong Sustainability

A crucial distinction is between ‘weak’ and ‘strong’ sustainability. Weak sustainability assumes substitutability between natural, human, and physical capital. From this view, environmental degradation can be offset through technological progress or monetary compensation. Strong sustainability rejects this substitutability, arguing that certain natural assets are irreplaceable and must be preserved for future life support. This has implications for how strictly or flexibly we define sustainability.

Sustainability in Practice

If sustainability is the goal, what actions does this necessitate? Proponents of weak sustainability point to innovations gradually relaxing constraints. However, strong proponents emphasize uncertainty and irreversibility risks that favor conservation. These differing perspectives inform very different pathways for achieving sustainability. For example, one may prioritize near-term economic growth while the other favors environmental protection even at short-term economic costs.

Distributional Equity Over Time

Solow’s paradox questions the “inconsistency” between concern for future generations’ welfare and attention to current inequality. This highlights tough choices around whether to focus resources on investments enabling long-term sustainability or redistribution for more equitable living standards today. There are good arguments on both sides, requiring difficult trade-offs.

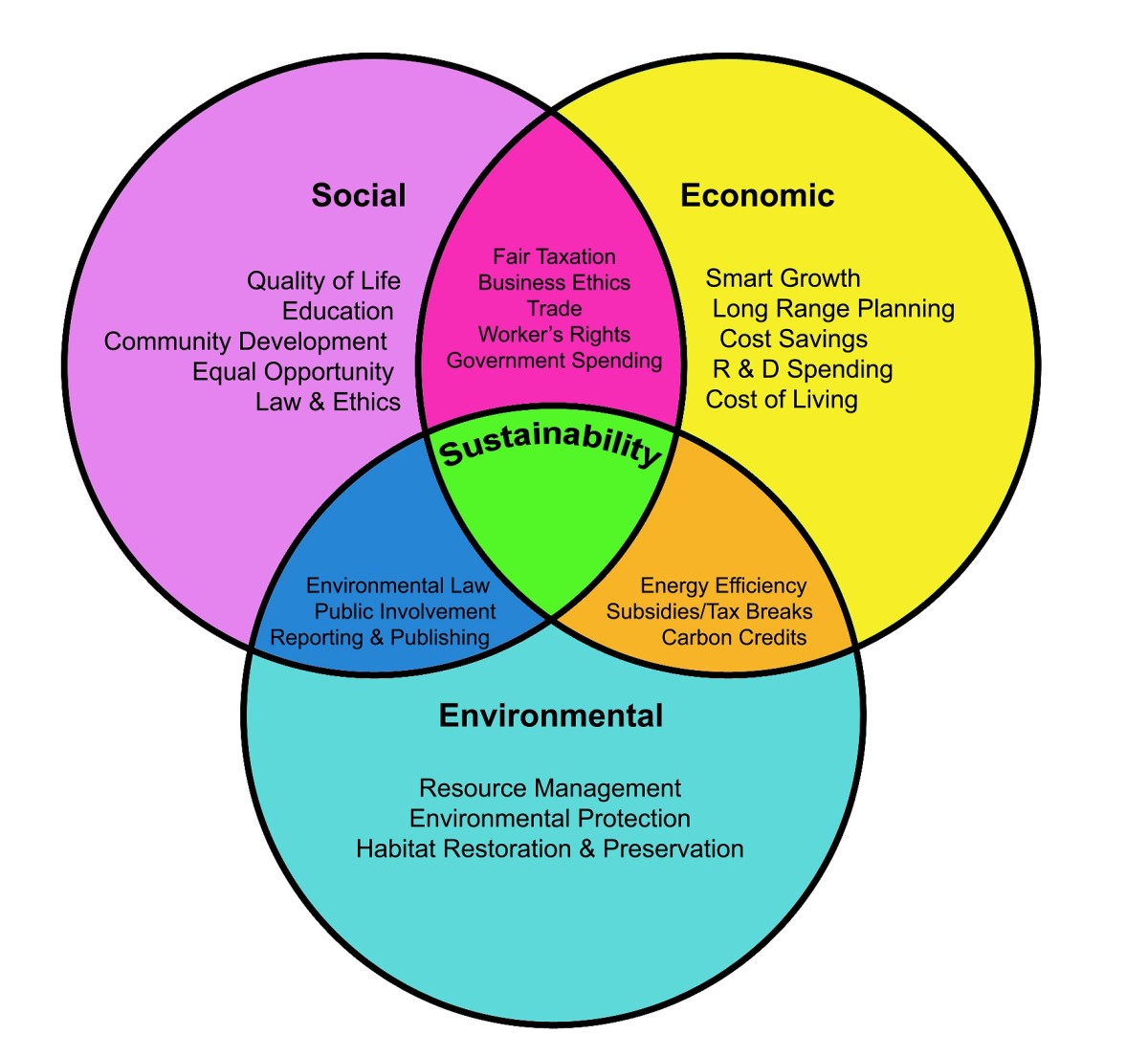

Sustainability Beyond the Environment

Ultimately, sustainability must be about holistic human well-being rather than solely the environment. Our individual and shared choices have cascading consequences, both beneficial and detrimental, across generations. Achieving sustainability demands awareness of our interconnectedness and carefully balancing complex, long-term economic, social, and ecological priorities. It is a profound challenge but also opportunity that sits at the heart of humanity’s shared future.